Yes I'm back. It's still probably going to be sporadic blogging for a while but something from my childhood popped into my mind recently and I wanted to share it. Although that title at the top sounds like it's from some obscure 1960s superhero comic - all lurid colours, x-ray specs adverts and checkerboard mastheads - once again this section of the blog is actually going to be about an educational TV program - something small that had a huge impact on my early life.

I went to school in the UK in the 1970s and early 1980s. There were no PC's or tablets. No internet. No mobile phones. Just a succession of "temporary" pre-fabricated classrooms that had been there for thirty years (the dreaded "demountables"), ramshackle outside toilets, desks like something out of "Just William", playground apparatus made out of cast concrete and teachers that were more frightening than any horror movie (Mrs Fairbrass I'm looking at you). When I moved to 'secondary' school I remember depressing grey buildings that would have been at home in any prison yard, a maze of corridors and wasted hours of sports lessons - all interspersed with a lot of bullying.

I'm being unfair. There were some good times during my school years and some excellent teachers. Mr McCarthy gave me my love of fantastical stories. Mr Keane gave me my interest in science. Mr Wheeler managed to instil a lifelong interest in World War II. Certain things that I learned have stayed with me ever since. More importantly, this was the peak period of ITV and BBC schools’ television programmes.

Most primary and secondary schools were using them in lessons at some point. It was the highlight of the week, in both my schools. My abiding memory is that there was a kind of ritual that had to be observed. The class would be escorted into the tiny "television room" (basically a dour windowless cubicle somewhere in the middle of the school building with the requisite number of grey plastic chairs) and told to sit down and behave. The teacher would then toddle off to the locked store cupboard next door to collect the television (it being a far too precious a commodity to be left out unguarded) - at which point of course the class would do anything except sit quietly and behave (unless it was the deputy head because even the most disruptive pupils were scared of *him*).

Before World War III broke out the teacher would return wheeling in the precious box, replete on its sturdy metal stand and enclosed in a wooden box (why?). With a practiced action they would slide back the folding doors of the cabinet to reveal the behemoth inside. The screen must have been all of twenty inches at its utmost, humming into life with a warm glow from the valves and the ever-present smell of burning dust.

The early days were before the advent of video recorders - although they did arrive eventually when I was around twelve, and you were privileged indeed if you were allowed to push the "play" button. Not yet for us the convenience of watching a program when it suited the school. We had to be there at the time of transmission or not at all. Like a producer at his mixing desk, someone in the mysterious locked room at the back of the library (they'd call it a 'media lab' or something equally grand I expect) would flick a switch to allow the signal through to the darkened room and the screen would sputter into life to show the familiar clock, counting down the sixty seconds til the programme began...

Like junior scientists at NASA Mission Control, we would sometimes be allowed to count down the last ten seconds together out loud. Silence was then meant to descend, but inevitably some jokester would shout out "Blast Off! - to a groan from his classmates and a stern "Shush!" from Mr Wells. By the way, that's not a random image I've picked there to illustrate ITVs timekeeping - the programme named above is key to the memories I am recalling here.

"Picture Box" was the jewel in ITVs schools programming, running for an astonishing twenty-seven years. Beginning in 1966 it was created by Brian Cosgrove of "Danger Mouse" fame and initially presented by Dorothy Smith. It showed a huge variety of dramatic short films and documentaries in ten minutes slots, designed to stimulate the imagination of children and inspire creativity. This was the show where you learned how they painted the Forth Road Bridge, discovered the Legend of Sleepy Hollow, watched the French classic "The Red Balloon" or slipped into the bizarre world of Czech animation (there seemed to be a lot of that on TV in the 70s).

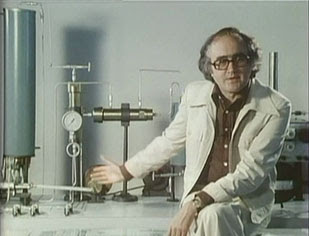

Of course the golden age of "Picture Box" - and the one that everyone remembers - is when it was presented by the affable Alan Rothwell (an actor who has popped up on both "Coronation Street" and the original Channel 4 soap opera "Brookside") - accompanied by that eerie theme music and an image of a rotating jewellery casket. As far as inducing childhood nightmares goes, that music is up there with white-faced clowns, the "Tales of The Unexpected" opening titles, Noseybonk and "King of the Castle" (well for me anyway). It also made the case of the television resonate for some reason...

For a long time as a youngster I kept getting Alan Rothwell and Doctor Who actor Bernard Holley (Tomb of the Cybermen & Claws of Axos) mixed up, even though they really don't look anything like each other. Similarly for "Mission: Impossible" star Peter Graves and Brit actor John Woodvine. I've also read that some children of my era felt than dear old Alan was "creepy", which I could never work out. It's strange how the mind works...

But I digress. "Picture Box" showed a number of these short films repeatedly throughout the school year (so that everyone could catch them). "Peter and the Wolf" and that damn "Red Balloon" kept cropping up. I have memories of tumbleweed rolling across a desert and a little boy launching a tiny hand-carved boat on a river, along with documentaries about windmills, the cuckoo, and shire horses on stamps (yes really!). However, the one film that I remember above all others is "Cosmic Zoom".

Made by the National Film Board of Canada in 1968 and drawn and directed by the brilliantly named Eva Szasz, it was based on a 1957 essay by renowned Dutch educator Kees Boeke. The original work attempted to illustrate the relative size of everything in the universe from the galactic to the microscopic, and the film does the same thing, through an eight minute long 'animated' sequence.

The film starts with a live-action shot of a boy rowing on a lake in front of some kind of industrial plant - his faithful dog beside him. The image then freezes and turns to animated form and the camera zooms out, revealing more and more of the landscape until we can see the whole lake, then towns and cities and continents and eventually the entire Earth. It then keeps zooming out past the Moon and the planets of the Solar System, past the vast black distances between stars and beyond our Milky Way and the myriad other galaxies - out into the farthest reaches of the universe. Eventually we slow down, stop and then a fast reversal begins, back through the inter-galactic vastness to Earth and to the boy on the boat.

The inwards movement doesn't stop there though. We keep zooming in closer and closer til we see a mosquito on the boys hand. The camera moves past the surface of the insect and under it's skin, through the blood vessels and into the microscopic world. Eventually we reach an atomic nucleus, and the process is reversed once again, so we zoom back to the boy in his boat, where he continues his interrupted rowing.

Look, as much as I can describe it, there is no substitute for seeing it for yourself -

Admittedly the drawings and animation were crude by the standards of the 1970s. I'm fairly sure that I was aware of the concepts presented within the film at a young age (being the avid SF reader and Doctor Who fan that I was). My memory is a bit blurry, but by the time I first came across "Cosmic Zoom" I think I would have been around eight or nine, so I am sure I must have seen the 1966 movie "Fantastic Voyage" (I *know* I'd watched the wonderful Filmation cartoon series - a blog post about the 'Combined Miniature Defence Force' must be on the list at some point). The delights of Star Wars, Battlestar Galactica, Buck Rogers, Blake's 7 (and Doctor Who's "The Invisible Enemy") were only just around the corner.

But none of that mattered. Something about this simple little film entranced me. Here was the vast scale of the micro and macro-scopic universes laid out in a way that everyone could understand. My imagination and interest was fired up even more than before and I began to scour the local village library for information. There wasn't a great deal to choose from in such a small resource and it was somewhat limited, but nonetheless I read everything, kept looking for more. I watched all the factual science show on the BBC - "Tomorrow's World" was already a staple in our house but I tuned into "Horizon" and "The Sky At Night" and of course "Connections". I must have driven my parents mad. It was a wonderful time in my childhood.

Then when I was ten I saw a second, almost as influential, film that covered very similar ground to "Cosmic Zoom", but perhaps from a more 'mathematical' slant. "Powers of Ten" began life as a black and white prototype short in 1968, from the minds of Charles Eames and his wife Bernice (known as Ray) - pioneers of modern architecture and furniture (many people will have heard of the Eames lounge chair). It depicted the scale of the universe according to an order of magnitude based on the factor of ten, using that same famous "Cosmic View" book by Kees Boeke as its inspiration. However it was the second revised colour film completed in 1977 that most people became aware of.

Titled "Powers of Ten: A Film Dealing with the Relative Size of Things in the Universe and the Effect of Adding Another Zero", the documentary begins much like "Cosmic Zoom", with a static one metre square view of a scene on Earth - this time a man and woman picnicking in a Chicago park. Slowly our perspective pulls back to a view ten metres across (101 m) and then a hundred metres (102 m), where we see the whole park, and then one kilometre (103 m) to reveal the whole city. Further and further we recede adding more zeroes to the distance until we reach 1024 m - a hundred million light years from Earth - the size of the observable universe. The process then reserves, smaller and smaller to views at negative powers of ten (10-1 m being 10 cm for example), into the sub-atomic world and finally the camera stops at 10-16 m - 0.00001 angstroms - the home of quarks in a proton of a single carbon atom. Wow.

With narration from MIT physics professor Philip Morrison and music by Elmer Bernstein, this was a big advancement on "Cosmic Zoom". Not only were the graphics better but the addition of scientific notation and measurements gave an even greater sense of scale. Once again I was mesmerised. This exuberant fascination with the universe lasted well into my mid-teens, alongside my love of science fiction and - strangely - a growing interest in the paranormal. I sometimes wonder if I missed my calling in life. Perhaps I should have pursued my interest in science and followed my hero Carl Sagan (there will be *much* more on him another time) and become a cosmologist or astro or particle physicist. Maybe I could have been the one to discover the "Theory of Everything"? Ah well, it was not meant to be...

The Eames film must also have had an impact on many others too, as over the years there have been several more updated and enhanced versions. In 1996, Morgan Freeman narrated "Cosmic Voyage" a loose remake presented in IMAX at the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C. In 35 minutes it managed to show forty-two orders of magnitude, plus some brief commentary on the Big Bang, black holes and particle acceleration. It was also nominated for an Academy Award. You can watch that one here as it's a bit too large to embed.

Then in 2012, astrophysicist Danail Obreschkow developed a complete remake of Charles and Ray's film using state of the art computer imaging, but this time as an Apple iOS application. "Cosmic Eye" uses real photographs wherever possible taken from telescopes and microscopes and its CGI is based on the latest scientific knowledge. In just a few decades the scale has now been expanded and defined outwards to ten billion light years and inwards to one "femtometre". It's well worth downloading, but if you want to watch a film generated from the App, you can see it here.

Finally I can't leave out the opening sequence of the Jodie Foster-starring "Contact" (that Carl Sagan gets everywhere) which is clearly inspired by "Powers of Ten".

What all these films have in common is a desire to show the scale and wonder of the universe we live in, from the largest supernova to the tiniest atom. The earliest ones inspired me and the latest ones will hopefully do the same to a new generation.

Let's zoom...